READ: How to Talk to Your Loved Ones About the Vaccine

10 hard-earned recommendations from the trenches.

“Of all the people I expected this from, YOU were definitely not one of them.” I said, exasperated.

I had known this friend for a decade—he and I had gone to college together. We even took science classes together! It’s why I was so surprised when he told me casually on a catch up Zoom that he was going to “wait and see” on the vaccine.

From the jump, wrong information has plagued our response to the pandemic. I’m not going to list the zany and downright absurd things people have shared lest I inadvertently spread wrong information myself. But as I wrote last week, it frames so much of our society’s reticence to just wear a mask or to recognize that lockdowns are sometimes essential to preventing viral transmission. That’s because wrong information thrives in chaotic, fearful situations. When demand for something outpaces its supply, something else is going to step in to meet the unmet demand. The same is true for information. People want answers to questions to which there simply aren’t answers—and in the absence of true, scientifically-based information, they sometimes believe the falsehoods.

Here’s what frustrated me about my discussion with my friend that day: I knew better than to chastise him. He was a victim, not a villain. And it’s not helpful. After all, as a public health communicator, I try to lead with compassion, empathy, and respect. I’ve had a lot of practice: I’ve been talking about COVID-19 since the first few cases were discovered in Wuhan, China. At that point, I was preparing for the publication of my first book Healing Politics, calling for a politics of empathy to heal our insecurity. Little did I know how profoundly our insecurity was about to be exploited by this once-in-a-century pandemic. And how critical empathy would be to our response. And yet, here I was, breaking my own recommendations for talking to people I care about about the vaccine.

So I’m writing these ten recommendations down in the spirit of humility, as much a reminder to myself as what I hope might be some helpful guidance for you. I’m not going to dig into specific arguments here, but rather frames of mind that I think are really important when communicating about the vaccine specifically, and the pandemic more generally.

- Not all who are misinformed are misinformants. This matters because it changes the way we think about them. Most people are just misinformed—they are victims of people who are spreading misinformation. They may inadvertently spread wrong information themselves, but they are not doing so maliciously or widely. The problem is that we usually treat misinformed people as misinformants—blaming them for their own victimization. If we, instead, think of them as victims of the act of misinformation, it’s a lot easier to have empathy for what they are going through.But that’s different from disinformation—which implies knowingly sharing wrong information, usually for some kind of pecuniary gain. These are the quacks, the snake oil salesman that so often proliferate in moments like these. People who spread disinformation aren’t simply misinformed. They are intentionally spreading wrong information, and these people don’t deserve our empathy—they need to be held accountable. If you run into actual disinformants, it’s usually best to reach out to the victims of their disinformation unless you have some power to stop them.

- Acknowledge fear. Almost everyone who is duped by misinformation is vulnerable to it because of their fear. They fear the lack of information. They feel powerless, and that scares them. They fear that they are being taken advantage of by people in positions of power. And fear is a completely normal response to a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic that has killed over 460,000 people in our country alone! Acknowledge that. Most will willingly accept they are fearful. Some will try to argue their fear is something else, like skepticism, or “better information.” That’s okay—name the fear anyway. They’ll find it.

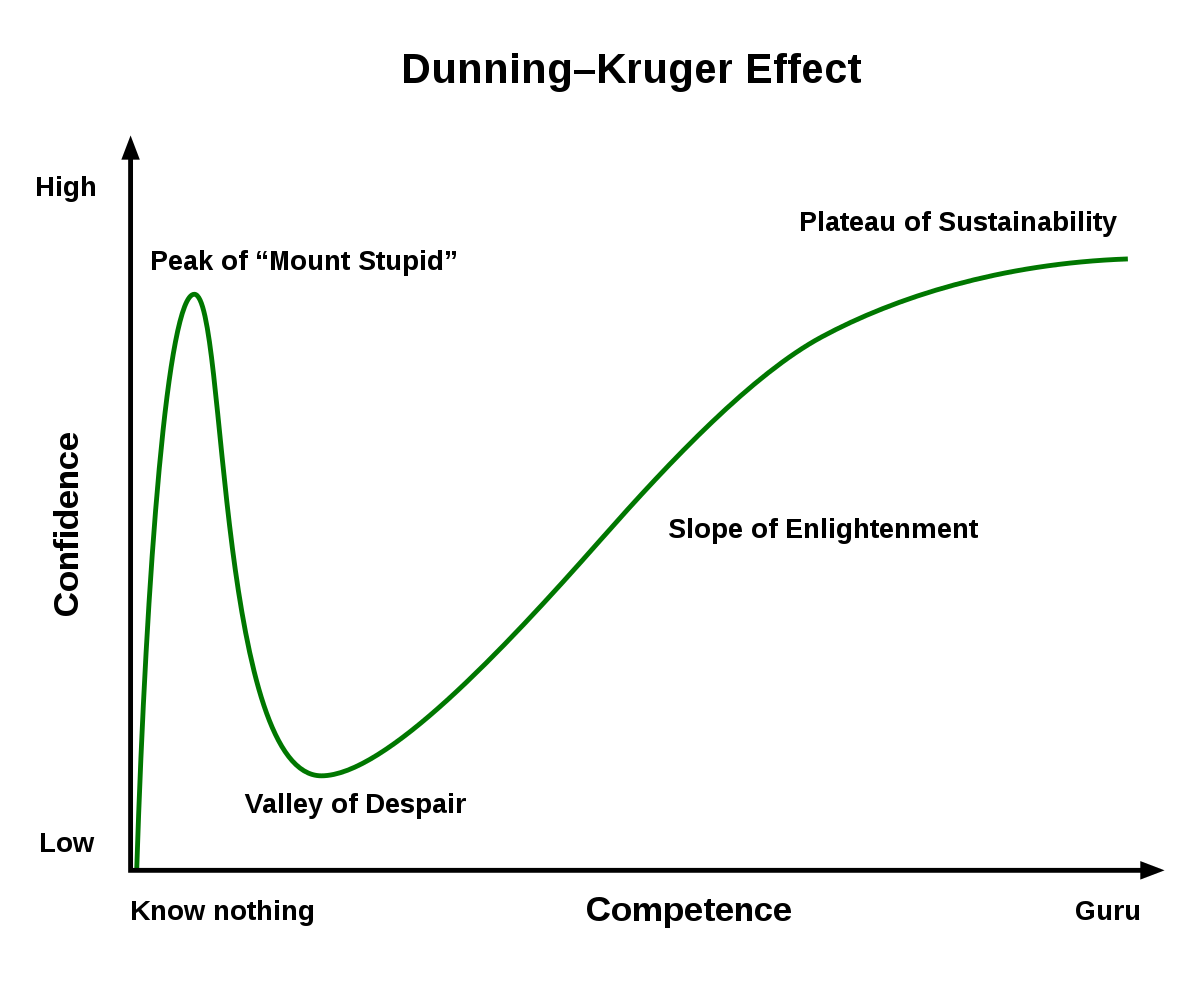

Ignorance is usually confident. Most people misinform because they speak without knowledge. It’s helpful here to describe what psychologists call the Dunning-Kruger effect. It’s the observable and consistent pattern that people who know the least about a thing tend to be the most confident in sharing it. And that’s because learning usually involves appreciating how much is simply not known about a thing, and then coming to understand how much of what is known one actually knows herself. Unfortunately, a lot of misinformation can be accounted for by people with little knowledge confidently and widely sharing a perspective that is, in fact, untrue.

- Praise their skepticism and lean into it. After all, skepticism is the root of science. Science is not a body of knowledge, it’s a process of asking and answering questions. And every scientific question starts with skepticism about the current answer to the question we’re asking. Even once we think we have a better answer, scientists are trained to be skeptical about it, testing it and retesting it to make sure it withstands scrutiny. It’s good to be skeptical. But here’s the thing: the only antidote to skepticism is information. That’s why you shouldn’t push back on skepticism with empty platitudes like “trust science,” but instead, ask people to take their skepticism a step further—to read and learn even more. And then ask them to apply their skepticism everywhere—including to the misinformation they may currently believe. Science stands up to skepticism a lot better than pseudoscience. SubscribeShare

- Win the future not the argument. Sometimes, we have to acknowledge our own fear about the person with whom we’re talking. We worry that if they don’t vaccinate, or they don’t wear a mask, or they keep having their weekly bridge game, that they’ll come down with COVID-19...or worse. That fear leaves us holding our relationship hostage to the things we want the other person to do. We resort to “if you do X, then I’ll do Y” statements that back our loved ones into a corner. That forces them into a fear-driven fight or flight response. Neither fighting or fleeing helps. Put the relationship and your future influence ahead of the Hail Mary you’re trying to throw to achieve an outcome you can’t control anyway. Focus on your ability to win the future, rather than your desperation to win the argument today.

- Remind them you love and care about them. Because these arguments often become confrontational, what’s lost is the fact that you love and care for these people. Remind them that—remind yourself that! Connect them to your concern. Remind them why before you talk about what you think they should do.

- Provide context. Every medical decision we make is about a series of trade-offs between some pain, pathology, or risk thereof now, and some at some point in the future. You make the trade-offs that are worth it. Usually, the imminent experience of pain or pathology makes taking medications to treat them obviously worth it. You know what you’re trying to treat because you’re currently feeling it. Vaccines don’t treat a pain or pathology we’re experiencing right now, but seek to prevent us from having it in the future. That trade-off is only worth taking if we think we’re at imminent risk today. The problem is that we’re not always rational about the risk we actually face today. Most of us think that because something has not happened, that it will not happen. That “normalcy bias” tricks us into forgetting the real risks we face if we don’t act. You’ll find normalcy bias hidden in the arguments you usually hear from vaccine-hesitant people. “Well, what if…” they say, usually followed by some kind of bad thing they think could happen some time in the future if they were vaccinated. But what’s missed is the bigger risk of the alternative—of not being vaccinated. So remind them: we’re not asking anyone to take a vaccine in a vacuum. Instead, we’re asking them to take one in a global pandemic. And whatever fear your loved one has about some infinitesimally small risk of some unknown, unspecified outcome far into the future, remind them the very real, very possible risk of the alternative of not vaccinating: a far higher risk of serious illness or death to COVID-19 in the short term, and long haul symptoms in the long term.

- Empower them to make the right decision. When we question people’s choices, we implicitly undermine their trust in themselves. That can be painful. So to counteract that, remind them you trust them—that you believe in them to make the right decision.

- Take breaks, but come back. Finesse is a lot more powerful than force. The Grand Canyon wasn’t carved by a giant water cannon, just the gentle persistent passing of water over a long, long time. If the conversation gets hard, take a break. Pull away—because it’s about the future not the argument. And then come back when emotions have passed, and keep pressing on. Chances are your constant, gentle reminders will go a lot further than one big argument ever could.

- Replace anecdotes with data. Misinformation usually stands on the spindliest of anecdotes. “My friend who…” or “I heard about this one guy...” These kinds of anecdotes are extremely hard to argue against because they’re ripped from individual situations (often exaggerated or made up), the facts of which nobody really knows for sure. The best way to push back against them is to contextualize them in data—what actually happens, how often, and why. “Yes, some people do experience some symptoms of headache, muscle pain, and even fever. That’s a small number of people—and it’s proof the vaccine is working. Those are the feelings of your body’s immune system ramping up, recognizing the vaccine, and getting ready to battle the virus if it ever sees it! It only happens in a minority of cases and it always goes away quickly.”The most important antidote to misinformation is actual information. I recommend you read about the vaccines. I found the New York Times curated list of questions and answers particularly helpful. And if you really want to dig in, you can always go to the FDA’s own documents on the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines. If you’re not trained in the health sciences, it’s worth taking notes on questions you might have and asking someone with a bit more training.

Beating this pandemic is going to take a lot of people making a lot of good decisions. And that’s not just what we do, personally, but how we wield our influence among the people we love. As my own experience demonstrates, it’s hard to do gracefully. I wish I could say I follow my own recommendations all the time, but I fail sometimes. It’s in that humility of knowing that, that I try to find the empathy to do better next time. Onward.